|

|

|

|

The purpose of this article is to

explain how the provision of Special Education

developed over the years at the A B Ellis Public

School. There will inevitably be those who felt

that the school failed to meet the needs of their

child and those who felt the opposite. There are

students who felt they benefitted from the help they

received and others who would disagree. This

article doesn’t set out to present an argument one way

or another but to explain how over the years the

provision changed and developed. I want to also

make it clear that these are my memories and I take

full responsibility for any mistakes or omissions I

make as I cast my mind back more than 46 years.

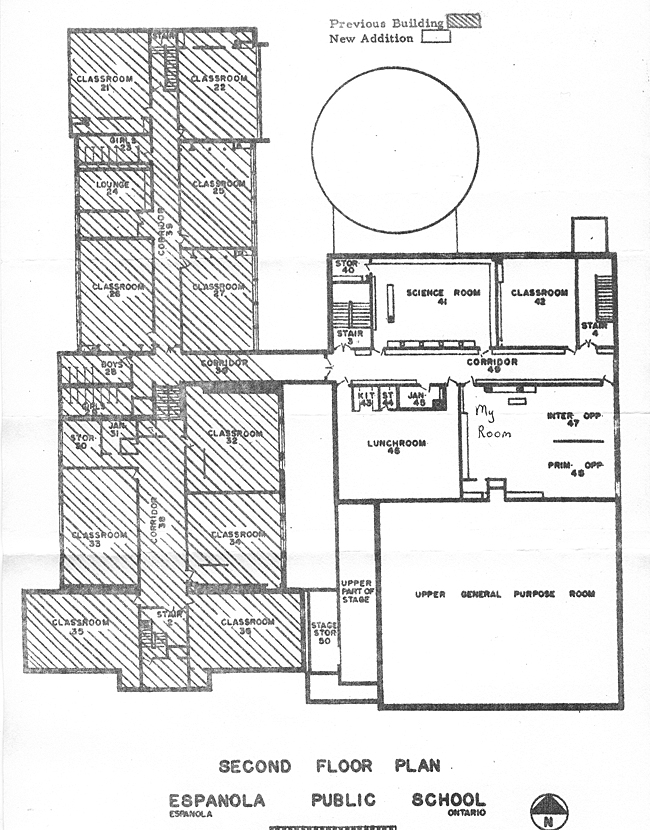

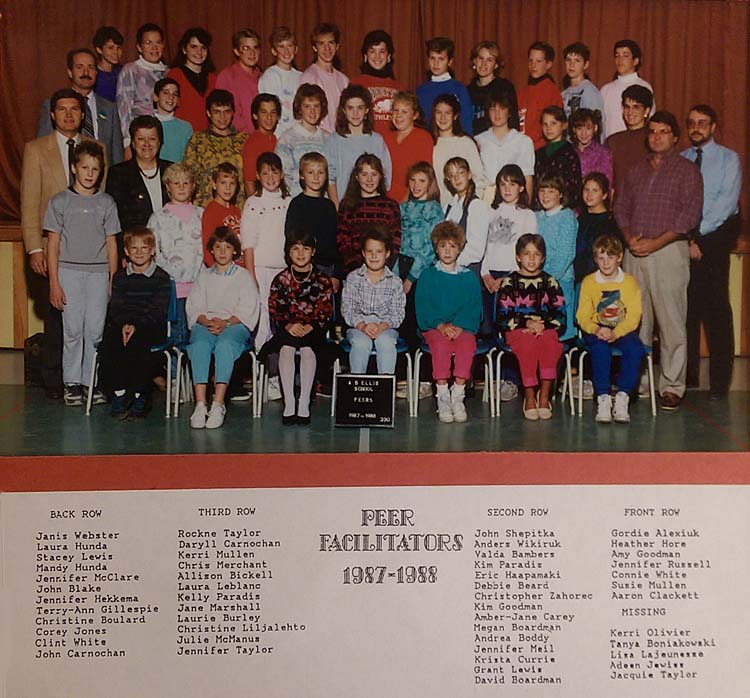

David BoardmanIn 1971 the school built a large extension which added a library, gymnasium, offices, a lunch room, classrooms and a large double room described on the plans as home to Primary and Intermediate “Opportunity” rooms.  The room came equipped with two large portable room dividers that were meant to provide a barrier between the two “rooms”. The term opportunity class was one that was about to go out of fashion in Ontario. Before I arrived at A B Ellis to take up the post of Special Education Teacher, I had worked in an Occupation class in Southern Ontario. It was a lovely well-equipped two-room school a stones throw from Lake Erie. The children were all, to various degrees, in need of special education support. The reason I left was that the Niagara Board of Education decided, as others did around that time, that those needs were best met without removing the children from the mainstream. That it was better for the children to be enrolled in an ordinary elementary school in age appropriate classes and to receive whatever support they needed in that setting. Despite the building drawings, this was Andy Ellis’s intention as well. He regarded the room as a “Resource Room”, staffed and equipped to reach out to a wide spectrum of children within the school so the room was never anyone’s home but a place for children to go for a variety of reasons. Andy’s vision was, in many areas of education, ahead of its time and not always understood or shared by others. As teachers our mandate was, as you might imagine, to reach out and help children with literacy and numeracy problems but he also wanted us to find ways to provide “enrichment” activities to other students giving them access to resources we had within the room. Ironically, years later the province would introduce legislation, commonly known as Bill 82, that would require schools to focus on the needs of what it termed “exceptional children”, a term which covered a wide variety of needs ranging from those with physical or intellectual challenges to the gifted and talented. Andy Ellis was about a decade ahead of the province in his thinking. In September 1971 we started out offering remedial services to children in all grades withdrawing them for periods of time each day to our offices located of the main staircase at the Spruce Street end of the old building. By January we had moved into our shiny new resource room in the extension and we set to work to put Andy’s vision into operation. This was a boom time for the school with the enrollment going up and class sizes going down. The trend was away from the large classes of the 50s and 60s towards much smaller classes, especially in the primary division. There were often three classes in each grade and certainly no split grades. This obviously added extra pressure to the Special Education department because finding a way to timetable children for remedial sessions from a growing number of classrooms, each with their own timetable, was a real challenge. Over time we came up with three solutions to this. The first was to use educational assistants to implement programs designed by the special education teachers. This made it possible for the children to get more frequent and more extensive help. Some of this happened in the resource room and some in the child’s homeroom. Because the school’s resources could only go so far, when it came to hiring educational assistants, we enlisted the help of parent volunteers. Some of these were parents of children in the school and others were people with some free time they were willing to share. At one point we had a large number of volunteers who worked with individual children or small groups, again in both the resource room and in homerooms. Finally, in later years we introduced a Peer Facilitator Program that harnessed the talents of children who showed a desire and aptitude to help others. We provided them with extensive and ongoing training and they were matched with appropriate partners or “buddies” with whom they met regularly. In some cases this involved help with academic needs but it was mostly designed to address more social needs.  For a period of time we became part of an initiative by the Ministry of Education to add speech and language services to all of our schools. Speech and Language Pathologists came to the community to teach the resource teachers how to assess children with speech and language difficulties and design treatment programs to help them. The consultants continued to work alongside the resource teachers helping with assessment and programming and liaising with parents. Around that time the board also benefitted from psychological and psychiatric services from Sudbury. On a regular basis a team of professionals would visit Espanola to assess the needs of children and either make recommendations to the school for appropriate programming or offer direct support from members of their team. There were also occasions when it was decided that the school didn’t have the resources needed for a particular child and that a temporary place in a special school in the Sudbury area would be more appropriate. At the beginning of the 1970s most of the children involved in Special-Ed programs came from the Intermediate and Junior Divisions. However, in the 1976-77 school year the Special-Ed department turned its attention to the early identification of and appropriate intervention for children in the primary division. Concerns that some children were entering grade one unprepared to make the transition from Kindergarten to Grade One led to the introduction of our “Low Enrollment” program. We created one class that had a very small enrollment of children identified as needing intensive help. The classroom teacher was supported in this job by Special-Ed staff. In following years we extended the program into three classes spanning grades one to three. At the same time we introduced annual assessment in Kindergarten as part of the process of identifying those children who would benefit from this intensive level of support. While the program was effective in giving late maturing children a level of support and developing skills required in a regular classroom setting, the impact of the program on staffing resulted in it being discontinued following the 1983-84 school year. During the later years of the 1970s we started to offer enrichment programs to “gifted” children. This proved to be a difficult task. The first issue was identification because our resources were limited and it was important to make sure we were using them wisely. Finding children who were struggling to learn to read or develop numeracy skills, or those whose behaviour made learning difficult, was a relatively easy task. Finding children for whom the classroom program failed to challenge their abilities was a different matter. In the beginning we did this by asking classroom teachers to identify them but this wasn’t always a success. Teachers tended to identify a group of children who were high achievers and some of them were indeed children with advanced abilities. Some, however, were hard working children who found the kind of programs offered in an enrichment program a step too far. There was also the problem that some intellectually gifted children weren’t high achievers. Instead of applying their ability to the tasks presented in the classroom, some of them refused to engage and in some cases exhibited behaviour that was both disruptive and counter-productive. So eventually we abandoned that approach and started screening children with a series of tests given at the end of the primary division and combining that with information gathered from teachers. This was never perfect and probably failed to identify everyone but it was at least an attempt to be objective. Programming for gifted children also had its challenges. In the beginning we attempted to coordinate our programs with those offered in the classrooms the children came from. I remember in particular working with a large group of grade 7 and 8 students in the 1979-80 school year on a unit about First Nations culture. Ironically, assessment became an issue because some children were afraid that their ability to win academic awards might be put in jeapordy. They were confident that they could maintain high averages in the regular classroom program but were worried that their marks might be lower in a gifted program. Others had social reservations and like all teenagers preferred not to be seen as different. Clearly our challenge was to provide compelling programs that overcame these concerns and in the 1980s and 1990s our enrichment programming changed direction as I will explain later. Special Education services depended a great deal on the availability of staff to deliver it. As I explained above, it always involved teachers, educational assistants and volunteers. As the enrollment in the school increased so did the staff. Over time the number of special-ed teachers rose from 2 to 3.5 and parent volunteers were gradually added to be the addition of educational assistants. In 1979 we began to see the direction the Ministry of Education in Ontario was going to go regarding Special Education and in 1980 they introduced the Education Amendment Act 1980 known as Bill 82. It became a landmark in Special-Ed in the province. Its provisions included: 1. the responsibility of school boards to provide (or to agree with another board to provide) in accordance with the regulations, special education programs and special education services for their exceptional pupils (a special education program is defined as an educational program that is based on and modified by the results of a continuous assessment and evaluation of the pupil and that includes a plan (now referred to as an Individual Education Plan) containing specific objectives and an outline of the educational services that meets the needs of the exceptional pupil) 2. the establishment of Ontario Special Education Tribunals to hear appeals brought by parents and to make final and binding decisions concerning the identification or placement of an exceptional pupil. Bill 82 changed Special-Ed dramatically as I will explain in the next phase of the story. (Note: Until Andy Ellis retired in 1978 the school was called the Espanola Public School so technically it wasn't A B Ellis for much of the 1970s.) |